WHAT IS AUTHENTICITY IN MUSIC? (Asking for a friend!)

Is Bob Dylan authentic? And how about Jaques Brel? (Not to mention some ancient French music covers band..)

What makes a musical cultural icon authentic? Is it the recordings? Like prehistoric insects immortalised in amber resin, (they resinate! bof! ). Is it the story? the myth? the canon? or their famous works?- every detail pored over and dissected. Is it the cultural glue that links us all through our collective experience? Is it the substance of the song itself? – the chord progressions, the lyrics, the sounds, the melody… And how do we know (if we do) when it’s not authentic? I guess that brings into play, that cute little word, ‘opinion’; but surely the point of the authenticity concept is that it transcends opinion? I think it’s a very challenging and zeitgeisty kind of consideration in today’s cultural climate – where musical tribute acts are default, biopics flood the airwaves and a screenwriter’s job is often to provide a twist to an established trope. With the ability to record and archive almost everything, we live in a truly post modern world and as such, I’d say the act of bestowing authenticity is virtually akin to finding the meaning of life. Or, well! – a currency considered by many, as more valuable than money. (Just look at the fine art market, where people will pay through the nose for proven authenticity even if they can’t see the difference with their own naked eye.)

So, here we are, Boum! (aka: lesboum.com …ahem!); a group who plays mostly cover songs. We happened to be in London when we took shape and began choosing our favourite French songs to play to an English audience. (Interestingly, I just heard the Talking Heads explain they formed to entertain their friends playing covers of their favourite songs. Most bands don’t form with the intention of becoming unique. It’s more about riding a wave of musical enthusiasm) Of course, having a French singer and an accordion in the band influenced our choice of material quite a lot; it narrowed the pool of music we could draw from, but it didn’t narrow our horizons – quite the reverse, because unlike a band trying to navigate the nuances and stand out in their own cultural landscape, we didn’t have to take account of our brethrens’ opinions and just barged into the French cultural room like kids in a sweet shop.

It’s a weird situation for us Boumsters at the moment, because we don’t really consider ourselves to be a tribute band, or as having any kind of duty towards preserving a recognisable copy of the original songs we cover. This means we don’t really want our audience to come to hear us expecting to hear their favourite songs. We care deeply about the music and stories of the songs and go to great lengths to arrange them – but it’s more about the challenge of adapting them to our sound – developing a bond between the song and us – the energy we bring. This bond is where authenticity lies in my opinion.

For something to be authentic, you have to make it your own. You can go too far and make it too much your own – where the thing you are trying to articulate gets overwhelmed by the particular sound or stylistic interpretation you bring – maybe because your style is too generalised or too whiffy/ not appropriate. It’s a delicate balance between content and performance. (Interestingly, this interpretation isn’t so far from copyright law…)

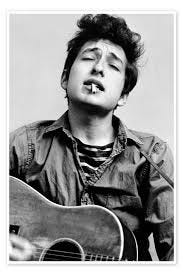

This reminds me a lot of the evolution of Bob Dylan (as described in his brilliant autobiographical book of musings – Chronicles, about which Dylan himself commented, “I’ll take some of the stuff that people think is true and I’ll build a story around that”.)

Bob is a great case study. He literally constructed his iconic vocal and musical style by flitting round the Eastern Seaboard of the US, finding his favourite musicians and extracting their unique tricks like a precious stone miner. His genius was in the bits he chose to copy and those he threw out. He was meticulous and analytical and most astutely, he was politically sensitive in his tastes. He shunned excessive flamboyance and kept in all the rough sounding bits – in fact he cultivated them. (I always found his collaborations with Joan Baez deeply weird in considering how manicured and whitewashed her sound was compared to his pointedly low brow – I think he must have mischievously enjoyed the clash.) However many musical status rewards were thrown in his path, he never wavered from his mission; to the point that we the public were mesmerised into thinking he was following an age-old trail. A natural phenomenon from the bowels of the earth. The irony is that he forged it – it was a construct of his imagination! As were the histories he spun into myth.

So: to the point! What really provoked me to write this blog was I recently went to the Old Vic in London to see ‘Girl from the North Country’, a play/ musical by Conor MacPherson inspired by Bob Dylan. The action centred around a great depression era scenario, with characters in a boarding house who might have featured in many of Bob’s songs. Theoretically, the show had everything. MacPherson is a playwright whose previous work I loved (The Weir, Shining City). And of course Dylan’s music and words. The band and the arrangements were scrupulous in their attention to detail. But, alas! For me, the whole production really missed the mark – it was an object lesson in what makes something inauthentic.

The musical arrangements faithfully took from the sounds – instruments/ chords/ phrases, from the original songs – but somehow managed to separate the components; (probably not helped by the different players being positioned at the four corners of the stage). Then the singers – and that was quite a large cast who all sang – prolifically well – too well! They just showed off their training too much. There was embellishment (it was clear we were existing in a post Beyoncé era) and much acknowledgement of the Black music (gospel, soul) traditions that undoubtedly would have been appropriate to some of the play’s characters and their journeys – but wait a minute! It’s like everyone failed to notice that the end product was nothing like the studied simplicity of Bob’s folk musical modesty. And the performers just couldn’t resist showing their vocal range in terms of power, polished tone and diversity of growl. I just don’t understand how you could go to all the trouble of trying to capture the quintessence of Bob Dylan’s legacy and then fancy it up with ensemble arrangements like it was Oliver in the West End! Ah well! What do I know? A good portion of the audience seemed to think it was great!

I don’t mean to be mean. It’s not like it’s easy to achieve the authentic. I’ve done so many performances where I’ve felt like a charlatan or a performing monkey or where all the ingredients have been there, but it just sounded a bit flat. That balance between the essence of the music and the sincere energy of the performer is tricky to achieve. One can easily consume the other. And then there’s the audience. Sometimes you might put in the most genuinely authentic performance of all time – but no one was listening. They didn’t notice! Maybe those experiences are the most important, because then you have to summon your personal relationship with the music and value that. (As we all know these days, hunting for ‘likes’ can be a soul destroying experience.) On other occasions, they might be so predisposed to adoring the performer or idea of them that they are not able to be present and lose all critical faculty. How can all these people applauding with tears in their eyes be wrong?

I’m sure Jaques Brel often felt like a pastiche of himself. Trying to summon that crafted intensity night after night can’t have been easy and if you do end up going through the motions, the end product can subtly flip into sounding a bit cheesy. Even being the music’s creator, doesn’t bestow authenticity into your performance. Thankfully, Jaque’s commitment was so unwavering that his performing life (and death with his dogged commitment to smoking) was an object lesson in authentic self belief. He’s almost a bench mark for it.

Interestingly, like Bob, Jaques worked really hard to construct his unique identity and was at pains to distance himself from his bourgeois origins. But, also like Dylan, the more successful you are at achieving your USP, it can also result in the formation of an army of awestruck followers, no longer capable of discerning an authentic performance and who are more than happy to make up the missing 10% authenticity courtesy of their own unquestioning belief.

I find it wildly ironic, how almost as soon as an original new voice emerges, hero worship and popularity work to undermine the authenticity from which it sprang. Just like power corrupts, success undermines the real thing. This process has become ubiquitous in our postmodern world. The business of imitation has literally become so possible that it’s now default. We can’t keep up with the light speed travel of memes and reproductions. However much we crave it, beyond our own individual taste bubbles,we, as a society, are really struggling to recognise the authentic.

To some weird extent, I think authenticity is about being pig headed. Ignoring the noise. Having been there as a teenager when the British punk scene emerged, I have a soft spot for that quality of irreverence. It was refreshing. I didn’t want to bow down to the ‘genius’ of ABBA. (In retrospect, I think they did have some charm, but at the time, their sound made me feel like I was being brainwashed by some horrible evangelical cult.)

Irreverence is an attitude that I feel is essential to the Boum approach to French music, (and very possibly one not so available to the French themselves). It’s a circumstantial thing. You need to naturally find yourself in a setting where you don’t care. In some ways you have to reject the legacy of famous artists we borrow from. It’s not the actual music or meaning of the song we’re rejecting – or the attitude of the original performance. It’s the reverence, the noise, the collective preciousness that somehow, this or that song is ‘great’. Or you shouldn’t dare to sing it, because you’re never going to be as good as Brel! It’s not helpful to acknowledge music as the ‘best ever’. That’s a vibe killer.

Of course, I know I’m talking rubbish when I watch my youthful daughter enjoying new (to her) music with fresh ears. But then again, maybe not; because novelty is that circumstance of which I’m speaking. Is authenticity actually novelty? Oh my gosh! It’s another can of worms! Maybe that’s for another blog… 😀